Shaping Pain: The Art of Yoram Guenniche

- Caroline Haïat

- 2 days ago

- 5 min read

Amid global political and geopolitical tensions, wars and breaking news, but also the intimate suffering he encounters daily in his physiotherapy practice, Franco-Israeli sculptor Yoram Guenniche draws his inspiration from the reality surrounding him. Having settled in Israel following his aliyah in 1989, he developed an early passion for art and craftsmanship. Yet it was only after a traumatic event, some ten years ago, that he decided to devote himself fully to sculpture. It became both an outlet and a path toward healing — a second language through which he could express anger, doubt, disagreement and incomprehension in the face of a life marked by uncertainty. Portrait.

“Since 1993, I’ve practiced manual therapy. I know the human body intimately, and I draw inspiration from the bodies and the suffering of my patients to create my sculptures,” Yoram explains.

A devotee of extreme sports, he long lived for downhill mountain biking, freefall and skydiving, logging more than a thousand jumps. But in 2016, everything changed. During a jump, he witnessed the death of a close friend. “I was right behind him, jumping alongside his brother. I had just become a father, and I began questioning whether I could continue these extreme practices,” he recalls. He needed to find an alternative capable of replacing his addiction to risk.

Sculpture soon emerged as the obvious answer. It became an escape. Yoram naturally turned to iron — a material that gave him the sense of danger and tension he had once sought.

“A welding machine was given to me for my birthday, and steel quickly became my material of choice. After a short training course, I decided to experiment on my own, to develop my own language and tools. Drawing on my knowledge of anatomy, I build a skeleton — often from scrap metal — which I then cover with layers of welding. The process is painstaking, but the sensation it produces is unique,” he says.

An alternative language

Sculpture allows Yoram to shed the suffering he absorbs on a daily basis. Many of his works give form to pain, which he manages to transform and release through creation. In his forty-square-meter studio at home in Kochav Ya’ir, he dedicates every Tuesday to sculpture, along with hundreds of additional hours whenever the works “call” to him. It is within this intimate space that his most singular ideas take shape.

One of his pieces, Help, depicts two hands forming the silhouette of a boat. They rest on a block representing the sea, within which silhouettes appear — symbols of those who drowned. The work conveys the suffering of people forced to flee the places they once lived, sometimes at the cost of their lives.

This tragedy, largely underrepresented in public debate, has claimed tens of thousands of victims: several years ago alone, nearly 40,000 people died at sea. Faced with this reality, the artist felt compelled to translate the tragedy into sculptural form. The two hands embody a dual symbolism: the fragile vessel itself, but also the idea of help, hope and solidarity — all so desperately lacking for those who take to the sea.

An ambitious project to fund military equipment

For the past two years, Yoram has been placing his talent at the service of a collective exhibition bringing together amateur and professional artists, with the aim of raising funds for the Keren Or Cesaria association. The organization finances essential equipment for soldiers, including bulletproof vests and helmets fitted with night-vision systems.

Using metal salvaged by Yoram and other artists, several works were created, including Steel Alive and Circus of Terror. The artistic and solidarity-driven project raised 700,000 shekels through the sale of artworks exhibited in Caesarea and at the Rabin Center in Tel Aviv.

This year, the theme of the exhibition at the Rabin Center was rebirth. For the occasion, Yoram created two sculptures depicting pregnant women, entitled Hope — symbols of life re-emerging after the long period of war Israel has endured since October 7.

The monumental piece required more than 700 hours of work spread over seven months. “It was a real challenge,” he says. “The belly had to be luminous and at human height. I ended up with a sculpture standing 2.30 meters tall and weighing 260 kilos. It was extremely difficult to sculpt and handle — almost insane — but I rose to the challenge and I’m very proud of it.”

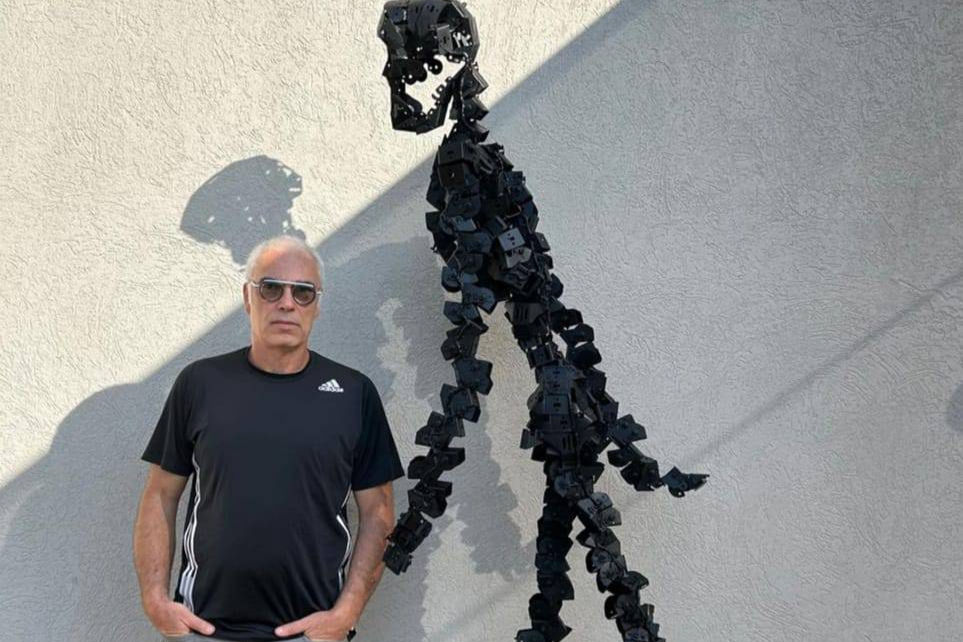

Using fragments of helmets, the artist also created Wandering, the figure of a man in motion, continuing to walk forward despite a partially charred body. Here again, the message is clear: that of a nation with no choice but to keep moving, to continue fighting and pressing ahead despite adversity.

Eclectic themes

Many of Yoram’s sculptures are directly inspired by his personal life. Love, for instance, reflects his vision of love through the figure of a musician embracing his instrument in a gesture that is both tender and fused.

Another work, K, evokes a kiss but radically subverts its meaning. “We’re sold the idea that we must all love one another, but this is the serpent’s kiss — it kisses you while strangling you,” the artist states, explicitly referencing the judicial reform that divided the country in recent years.

In K, Yoram Guenniche chose to depict two heads confronting one another. The image remains deliberately ambiguous: it is unclear whether this is an act of love or a clash. This indeterminacy embodies a love-hate relationship from which escape seems impossible.

Among his most personal works is Aspiration, a butterfly-shaped sculpture symbolizing the effort required to change, to evolve and to step outside one’s comfort zone. Created during the Covid period, it took a year and a half to complete and remains the piece to which the artist feels most attached. It evokes suffering, the will to surpass oneself, to break free. “It’s a bit like a swimmer lifting his head above water,” he says — a vital gesture of survival.

Begging is undoubtedly one of Yoram’s most emotionally charged creations. During an exhibition held at his home four years ago, a man stood in front of the sculpture for a long time before breaking down in tears. He insisted on buying it, explaining that it reminded him of his father, a former beggar on the streets of Berlin after the Shoah. “When he saw this powerful iron hand frozen in a posture of begging, he immediately thought of his father,” Yoram explains.

The work dedicated to the Shoah represented a true emotional ordeal for the artist. “It was extremely moving,” he says. The sculpture depicts a hand gripping a staff — which can be perceived as an arm, another body or a tree. The tree, a symbol of life, oxygen and balance, also refers to deforestation, to a “Shoah of trees,” which the artist draws in parallel with human catastrophes.

One hand reaches toward the sky, imploring help, while a trunk cut at the base clings to the last surviving tree, or attempts to pass on the energy it draws from the soil. The work is deliberately humanized, encompassing both human and natural tragedies. Emotionally overwhelming, the project forced the artist to work in parallel on another series, Connection / Disconnection, which materializes the inner storm behind this creation, with a disconnected figure placed at its center.

His next exhibition project aims to give artistic form to the dreams of wounded soldiers. Scheduled between April and September, the initiative is still seeking a venue. In it, the artist explores a more abstract approach — a territory he had previously approached with hesitation, but toward which he now feels naturally drawn.

Deeply affected by the current situation, Yoram Guenniche claims a humanist commitment. “If, through my art, I can help move things forward, bring a little humanity, then I will have succeeded. I want to reach as many people as possible and encourage them to ask the right questions,” he concludes.

Caroline Haïat

Comments